May 30, 2008

American fury in the Philippines. XLVIII / Cienta

March 16.- Instructed Lieutenant Colonel McCaskey, commanding Twentieth

U. S. Infantry, at Pasig, to clear the country in his immediate

vicinity of any of the insurgents who might be lurking near, and soon

after received a dispatch from him that he had sent out two battalions

to be deployed as skirmishers to clear the island of Pasig. Soon

after, heavy and long-continued firing was heard to the east and north

of Pasig. At 12 M. learned that Maj. William P. Rogers, commanding

Third Battalion Twentieth U. S. Infantry, had come upon the enemy,

intrenched one thousand strong at the village of Cienta, and that he

had carried the intrenchments and burned the town, the enemy flying in

the direction of Taytay.

Title: The official records of the Oregon volunteers in the Spanish

war and Philippine insurrection,page 547

U. S. Infantry, at Pasig, to clear the country in his immediate

vicinity of any of the insurgents who might be lurking near, and soon

after received a dispatch from him that he had sent out two battalions

to be deployed as skirmishers to clear the island of Pasig. Soon

after, heavy and long-continued firing was heard to the east and north

of Pasig. At 12 M. learned that Maj. William P. Rogers, commanding

Third Battalion Twentieth U. S. Infantry, had come upon the enemy,

intrenched one thousand strong at the village of Cienta, and that he

had carried the intrenchments and burned the town, the enemy flying in

the direction of Taytay.

Title: The official records of the Oregon volunteers in the Spanish

war and Philippine insurrection,page 547

American fury in the Philippines. XLVII / Tondo

Report of Capt. R. E. Davis, Second Oregon U. S. Volunteer Infantry,

of Pursuit of Insurgents in Tondo, February 23, 1899.

MANILA, P. I., February 24, 1899.

Maj. PERCY WILLIS,

Commanding Second Battalion, Oregon U. S. V.

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of my company's

actions during the skirmish and advance to Caloocan from Tondo,

February 23, 1899:

After receiving your order to deploy as skirmishers and protect the

left flank of the line, we advanced steadily with short rests for

better fire facilities, using both individual and volley firing, as

position of our line and enemy would permit. We burned all houses in

our rear, after thoroughly examining them, and sent to the rear about

fifty male prisoners. After the last halt on stone bridge I was

ordered to cross the lagoon and advance in skirmish line toward

Caloocan, examining and burning all houses in our front. In carrying

out these instructions we could not find a single stand of arms and

very few knives of any kind, although careful search was made for them.

After reaching the railroad station about two miles north of Tondo we

relieved the Montana company holding the road, and, awaiting your

advance, halted for lunch. Up to this point the country was full of

houses, and we burned them all after sending about one hundred men and

women to the rear. As they were not armed or in resistance and our

force was small we did not put them under arrest.

To sum up events we killed probably about thirty insurgents, as we

counted twenty five in our front while advancing. We sent to the rear

fifty prisoners and burned nearly one hundred houses.

Our total casualties were a slight superficial wound on index finger

of left hand of Martin Hildebrandt. We had a force of fifty men with

Captain Davis and Lieutenant Dunbar in command. I can not speak too

highly of the conduct of the men, as my only difficulty was to hold

them back and prevent unnecessary exposure to fire.

Very respectfully, R. E. DAVIS, Captain, Second Oregon U. S. Volunteer

Infantry, Commanding Company E.

May 26, 2008

Rizal as American hero. I

Quien creó la provincia de Rizal? Parece que el gobierno colonial

americano. En 1902 ya hay una mención a ella.

Rizal is a new province containing a portion of the territory formerly

included in the province of Manila.

Title: Civil government for the Philippine Islands. Speech of Hon.

Julius C. Burrows ... in the Senate of the United States Wednesday,

May 28, 1902. page 14

Author: Burrows, Julius C. (Julius Caesar), 1837-1915

americano. En 1902 ya hay una mención a ella.

Rizal is a new province containing a portion of the territory formerly

included in the province of Manila.

Title: Civil government for the Philippine Islands. Speech of Hon.

Julius C. Burrows ... in the Senate of the United States Wednesday,

May 28, 1902. page 14

Author: Burrows, Julius C. (Julius Caesar), 1837-1915

May 25, 2008

American fury in the Philippines. XLVI / Reconcentration

And Mr. Bacon well says:

We are apt to think about the reconcentrado camps simply in connection

with sufferings which may be endured by those within the camps; and,

in the case of the Cuban reconcentrado camps, where there was not

food, then, of course, all the added horrors of that tropical climate

constituted one of the features of the reconcentrado camps. But the

greatest horror and the greatest suffering which are occasioned by the

reconcentrado camps is not the horror and the suffering within the

camp, but the horror and the suffering without the camp. When a

general prescribes a certain limited area within which he says all the

people must congregate, there must be the corresponding direction

which will enforce that order; and the corresponding direction is that

everything outside of those prescribed limits shall be without

protection, and, both as to property and life, be subject to

destruction. Only in that way can people be carried within the limits

of the reconcentrado camps. It is because life is unsafe out of them,

because life is almost certain to be sacrificed out of them, because

all property left outside is to be destroyed, because all houses are

to be burned, because the country is to be made a desert waste,

because within a camp is a zone of life and without the camp a

wide-spread area of death and desolation. That is what a reconcentrado

camp means. Do you suppose if there is an invitation to people to come

within a reconcentrado camp, that they are going to come there unless

they are forced there? Is there any way to force them except to say

that it is death to remain outside? Why, Mr. President, when the

limited area of a reconcentrado camp is prescribed, the people cannot

be collected and driven in there. The soldiers cannot go out and find

them and drive them in as you would a drove of horses. It is only by

putting upon them this order, this pressure of life and death, that

they are made to flee within the limits of the reconcentrado camps to

escape the torch and the sword that destroys all without. When a

general prescribes a reconcentrado camp,- and I am going, before I get

through, to read Bell's order to show that that is what it means,-

when a general prescribes a reconcentrado camp, he practically says

that everybody outside must come inside or die: he practically says to

his soldiers, Those who do not get inside shall be slaughtered; and

the practical operation is that those who do not get inside are

slaughtered.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

We are apt to think about the reconcentrado camps simply in connection

with sufferings which may be endured by those within the camps; and,

in the case of the Cuban reconcentrado camps, where there was not

food, then, of course, all the added horrors of that tropical climate

constituted one of the features of the reconcentrado camps. But the

greatest horror and the greatest suffering which are occasioned by the

reconcentrado camps is not the horror and the suffering within the

camp, but the horror and the suffering without the camp. When a

general prescribes a certain limited area within which he says all the

people must congregate, there must be the corresponding direction

which will enforce that order; and the corresponding direction is that

everything outside of those prescribed limits shall be without

protection, and, both as to property and life, be subject to

destruction. Only in that way can people be carried within the limits

of the reconcentrado camps. It is because life is unsafe out of them,

because life is almost certain to be sacrificed out of them, because

all property left outside is to be destroyed, because all houses are

to be burned, because the country is to be made a desert waste,

because within a camp is a zone of life and without the camp a

wide-spread area of death and desolation. That is what a reconcentrado

camp means. Do you suppose if there is an invitation to people to come

within a reconcentrado camp, that they are going to come there unless

they are forced there? Is there any way to force them except to say

that it is death to remain outside? Why, Mr. President, when the

limited area of a reconcentrado camp is prescribed, the people cannot

be collected and driven in there. The soldiers cannot go out and find

them and drive them in as you would a drove of horses. It is only by

putting upon them this order, this pressure of life and death, that

they are made to flee within the limits of the reconcentrado camps to

escape the torch and the sword that destroys all without. When a

general prescribes a reconcentrado camp,- and I am going, before I get

through, to read Bell's order to show that that is what it means,-

when a general prescribes a reconcentrado camp, he practically says

that everybody outside must come inside or die: he practically says to

his soldiers, Those who do not get inside shall be slaughtered; and

the practical operation is that those who do not get inside are

slaughtered.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

American fury in the Philippines. XLV / Rape

An anonymous letter signed " An Outraged Citizen" was addressed to

General MacArthur under date of February 26, i9oi, beginning:

It is simply horrible what the Macabebe soldiers are doing in some of

the towns.... The Macabebes are committing the most horrible outrages

in the towns and the officers say nothing, but, on the contrary,

punish and threaten any persons who make complaint.... Some twelve

days ago some Macabebes went into a house, and four soldiers raped a

married woman, one after another, in the presence of her husband, and

threatened to kill him if he dared to say anything. The war will never

come to an end this way, nor will the country be pacified. The people

are compelled to take to the woods.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

General MacArthur under date of February 26, i9oi, beginning:

It is simply horrible what the Macabebe soldiers are doing in some of

the towns.... The Macabebes are committing the most horrible outrages

in the towns and the officers say nothing, but, on the contrary,

punish and threaten any persons who make complaint.... Some twelve

days ago some Macabebes went into a house, and four soldiers raped a

married woman, one after another, in the presence of her husband, and

threatened to kill him if he dared to say anything. The war will never

come to an end this way, nor will the country be pacified. The people

are compelled to take to the woods.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

American fury in the Philippines. XLIV / Liruan

official report of Major Waller, dated Nov. 23, 1901, from which this

passage is quoted:

On the march to Liruan the second column, fifty men, under Captain

Bearss, in accordance with my orders, destroyed all villages and

houses, burning in all one hundred and sixty-five.

...I wish to work southward a little, destroying all houses and crops,

and, if possible, get the rifles from Balangiga. This plan has been

explained to the general, meeting his approval.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

passage is quoted:

On the march to Liruan the second column, fifty men, under Captain

Bearss, in accordance with my orders, destroyed all villages and

houses, burning in all one hundred and sixty-five.

...I wish to work southward a little, destroying all houses and crops,

and, if possible, get the rifles from Balangiga. This plan has been

explained to the general, meeting his approval.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

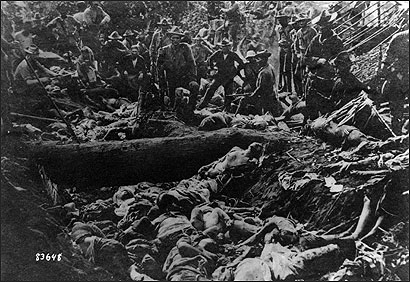

American fury in the Philippines. XLIII / Mass murder

Howard McFarland, sergeant, Company B, Forty-third Infantry, wrote to

the Fairfield Journal of Maine:

- I am now stationed in a small town in charge of twenty-five men,

and have a territory of twenty miles to patrol.... At the best, this

is a very rich country; and we want it. My way of getting it would be

to put a regiment into a skirmish line, and blow every nigger into a

nigger heaven. On Thursday, March 29, eighteen of my company killed

seventy-five nigger bolomen and ten of the nigger gunners.... When we

find one that is not dead, we have bayonets.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

the Fairfield Journal of Maine:

- I am now stationed in a small town in charge of twenty-five men,

and have a territory of twenty miles to patrol.... At the best, this

is a very rich country; and we want it. My way of getting it would be

to put a regiment into a skirmish line, and blow every nigger into a

nigger heaven. On Thursday, March 29, eighteen of my company killed

seventy-five nigger bolomen and ten of the nigger gunners.... When we

find one that is not dead, we have bayonets.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

American fury in the Philippines. XLII / Mass murder

L. F. Adams, of Ozark, Mo., a soldier in the Washington regiment,

describing the scene after the battle of February 4-5, 1899, said:

In the path of the Washington Regiment and Battery D of the Sixth

Artillery there were 1,oo8 dead niggers, and a great many wounded. We

burned all their houses. I don't know how many men, women, and

children the Tennessee boys did kill. They would not take any prisoners.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

describing the scene after the battle of February 4-5, 1899, said:

In the path of the Washington Regiment and Battery D of the Sixth

Artillery there were 1,oo8 dead niggers, and a great many wounded. We

burned all their houses. I don't know how many men, women, and

children the Tennessee boys did kill. They would not take any prisoners.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

American fury in the Philippines. XLI / Burning

Testimony of First Lieutenant Grover Flint,

...He testified further that he had seen hamlets, small towns of fifty

or sixty houses, burned by the American soldiers.... I saw it.... I

think the idea was at that time that the burning of these villages

would drive the people to the woods or to the towns,-a policy of

concentration, I think.... The people who lived in these houses were

apparently engaged in peaceful pursuits...

...He testified further that he had seen hamlets, small towns of fifty

or sixty houses, burned by the American soldiers.... I saw it.... I

think the idea was at that time that the burning of these villages

would drive the people to the woods or to the towns,-a policy of

concentration, I think.... The people who lived in these houses were

apparently engaged in peaceful pursuits...

American fury in the Philippines. XL / San Roque

Another charge grew out of a letter written by Corporal Williams as to

the looting of a village called St. Roque before June i, I899.

Williams, being asked, said that he wrote the letter, and that the

statement was "substantially true." The captain of his company stated that

the village of St. Roque was looted by the Iowa Regiment and the other

troops stationed at Cavite, that the men helped themselves to what

they found and destroyed articles of property they could not use, that

the colonel and other field officers did not exert themselves to stop

it, and that, while he disapproved of what was done, he did not feel

called upon under the circumstances to do anything about it. The

colonel and lieutenant-colonel stated that the town was burned by the

insurgents, and that the colonel ordered an officer to take charge of

the district, put out the fires, and collect and store all articles of

value. The colonel says, A part of the property so collected was

afterwards removed to Cavite for use of officers and men in the

quarters, which were found absolutely bare of furniture when my

regiment took station there.

the looting of a village called St. Roque before June i, I899.

Williams, being asked, said that he wrote the letter, and that the

statement was "substantially true." The captain of his company stated that

the village of St. Roque was looted by the Iowa Regiment and the other

troops stationed at Cavite, that the men helped themselves to what

they found and destroyed articles of property they could not use, that

the colonel and other field officers did not exert themselves to stop

it, and that, while he disapproved of what was done, he did not feel

called upon under the circumstances to do anything about it. The

colonel and lieutenant-colonel stated that the town was burned by the

insurgents, and that the colonel ordered an officer to take charge of

the district, put out the fires, and collect and store all articles of

value. The colonel says, A part of the property so collected was

afterwards removed to Cavite for use of officers and men in the

quarters, which were found absolutely bare of furniture when my

regiment took station there.

American fury in the Philippines. XXXIX / Extermination

"It was represented to me that the Filipino will not work; that even

when willing he can not work adequately; that increase of wages

merely enables him to enjoy more idleness, and that the introduction

of Chinese labor would act as a stimulus and by competition compel

him to work. I even met Americans (I am ashamed to say) who, in their

impatience at the slow-going Filipino, struck him or abused him with

violent language, and boldly declared that the only thing to do is to

exterminate him like the American Indian, replace him by Chinese, and

develop the country...

My professed friendship for the Filipinos and my indignation at such

un-American conduct on the part of not a few of my fellowcountrymen

compelled me to study this problem..."

David H. Doherty, 1904

when willing he can not work adequately; that increase of wages

merely enables him to enjoy more idleness, and that the introduction

of Chinese labor would act as a stimulus and by competition compel

him to work. I even met Americans (I am ashamed to say) who, in their

impatience at the slow-going Filipino, struck him or abused him with

violent language, and boldly declared that the only thing to do is to

exterminate him like the American Indian, replace him by Chinese, and

develop the country...

My professed friendship for the Filipinos and my indignation at such

un-American conduct on the part of not a few of my fellowcountrymen

compelled me to study this problem..."

David H. Doherty, 1904

American fury in the Philippines. XXXVIII / Genocide

CONCLUSIONS

From this review of the record certain things clearly appear:

I. That the destruction of Filipino life during the war has been so

frightful that it cannot be explained as the result of ordinary

civilized warfare. General J. M. Bell's statement that one-sixth of

the natives of Luzon - that is, some six hundred thousand persons -

had been killed or died of dengue fever in the first two years of the

war is evidence enough on this point, especially when coupled with his

further statement:

The loss of life by killing alone has been very great, but I think not

one man has been slain except where his death served the legitimate

purpose of war. It has been thought necessary to adopt what in other

countries would be thought harsh measures,

but which Secretary Root calls measures of " marked humanity and

magnanimity." *

2. That at the very outset of the war there was strong reason to

believe that our troops were ordered by some officers to give no

quarter, and that no investigation was had because it was reported by

Lieut.-Colonel Crowder that the evidence " would implicate many

others," General Otis saying that the charge was " not very grievous

under the circumstances."

3. That from that time on, as is shown by the reports of killed and

wounded and by direct testimony, the practice continued.

4. That the War Department has never made any earnest effort to

investigate charges of this offence or to stop the practice.

5. That from the beginning of the war the practice of burning native

towns and villages and laying waste the country has continued.

* This statement is confirmed by the official report made by the

Secretary of the Civil Government in Batangas, the scene of General

Bell's operations. He says that the population has been reduced

one-third; ie., from 3oo,ooo to 2oo,ooo by the war and its attending

conditions.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

From this review of the record certain things clearly appear:

I. That the destruction of Filipino life during the war has been so

frightful that it cannot be explained as the result of ordinary

civilized warfare. General J. M. Bell's statement that one-sixth of

the natives of Luzon - that is, some six hundred thousand persons -

had been killed or died of dengue fever in the first two years of the

war is evidence enough on this point, especially when coupled with his

further statement:

The loss of life by killing alone has been very great, but I think not

one man has been slain except where his death served the legitimate

purpose of war. It has been thought necessary to adopt what in other

countries would be thought harsh measures,

but which Secretary Root calls measures of " marked humanity and

magnanimity." *

2. That at the very outset of the war there was strong reason to

believe that our troops were ordered by some officers to give no

quarter, and that no investigation was had because it was reported by

Lieut.-Colonel Crowder that the evidence " would implicate many

others," General Otis saying that the charge was " not very grievous

under the circumstances."

3. That from that time on, as is shown by the reports of killed and

wounded and by direct testimony, the practice continued.

4. That the War Department has never made any earnest effort to

investigate charges of this offence or to stop the practice.

5. That from the beginning of the war the practice of burning native

towns and villages and laying waste the country has continued.

* This statement is confirmed by the official report made by the

Secretary of the Civil Government in Batangas, the scene of General

Bell's operations. He says that the population has been reduced

one-third; ie., from 3oo,ooo to 2oo,ooo by the war and its attending

conditions.

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

American fury in the Philippines. XXVI / Finish off

We advanced four miles and we fought every inch of the way;... saw

twenty-five dead insurgents in one place and twenty-seven in another,

besides a whole lot of them scattered along that I did not count....

It was like hunting rabbits; an insurgent would jump out of a hole or

the brush and run; he would not get very far.... I suppose you are not

interested in the way we do the job. We do not take prisoners. At

least the Twentieth Kansas do not.

--Arthur Minkler, of the Kansas Regiment

twenty-five dead insurgents in one place and twenty-seven in another,

besides a whole lot of them scattered along that I did not count....

It was like hunting rabbits; an insurgent would jump out of a hole or

the brush and run; he would not get very far.... I suppose you are not

interested in the way we do the job. We do not take prisoners. At

least the Twentieth Kansas do not.

--Arthur Minkler, of the Kansas Regiment

American fury in the Philippines. XXXV / Mass murder

A private in the Utah Battery:

"The cable news has kept the home folks fully informed as to the

progress of this 'goo-goo' hunt, so it is unnecessary to recount any

details of battles. The cruelties of Spain toward these people have

been fully discussed, but if the thing were written up by a recent

arrival here, he would make a tale just as harrowing. But the old boys

will say that no cruelty is too severe for these brainless monkeys,

who can appreciate no sense of honor, kindness, or justice.... With an

enemy like this to fight, it is not surprising that the boys should

soon adopt 'no quarter' as a motto, and fill the blacks full of lead

before finding out whether or not they are friends or enemies."

"The cable news has kept the home folks fully informed as to the

progress of this 'goo-goo' hunt, so it is unnecessary to recount any

details of battles. The cruelties of Spain toward these people have

been fully discussed, but if the thing were written up by a recent

arrival here, he would make a tale just as harrowing. But the old boys

will say that no cruelty is too severe for these brainless monkeys,

who can appreciate no sense of honor, kindness, or justice.... With an

enemy like this to fight, it is not surprising that the boys should

soon adopt 'no quarter' as a motto, and fill the blacks full of lead

before finding out whether or not they are friends or enemies."

American fury in the Philippines. XXXIV / Puente Colgante

Private Fred B. Hinchman, Company A, United States Engineers, writes

from Manila, February 22d:

"At 1:30 o'clock the general gave me a memorandum with regard to

sending out a Tennessee battalion to the line. He tersely put it that

'they were looking for a fight.' At the Puente Colgante (suspension

bridge) I met one of our company, who told me that the Fourteenth and

Washingtons were driving all before them, and taking no prisoners.

This is now our rule of procedure for cause. After delivering my

message I had not walked a block when I heard shots down the street.

Hurrying forward, I found a group of our men taking pot-shots across

the river, into a bamboo thicket, at about 1,200 yards. I longed to

join them, but had my reply to take back, and that, of course, was the

first thing to attend to. I reached the office at 3 P.M., just in time

to see a platoon of the Washingtons, with about fifty prisoners, who

had been taken before they learned how not to take them."

from Manila, February 22d:

"At 1:30 o'clock the general gave me a memorandum with regard to

sending out a Tennessee battalion to the line. He tersely put it that

'they were looking for a fight.' At the Puente Colgante (suspension

bridge) I met one of our company, who told me that the Fourteenth and

Washingtons were driving all before them, and taking no prisoners.

This is now our rule of procedure for cause. After delivering my

message I had not walked a block when I heard shots down the street.

Hurrying forward, I found a group of our men taking pot-shots across

the river, into a bamboo thicket, at about 1,200 yards. I longed to

join them, but had my reply to take back, and that, of course, was the

first thing to attend to. I reached the office at 3 P.M., just in time

to see a platoon of the Washingtons, with about fifty prisoners, who

had been taken before they learned how not to take them."

American fury in the Philippines. XXXIII / Finish off

In a letter to Mr. Herbert Welsh, of Philadelphia, an official of the

War Department says:

The aggregate killed and wounded [Filipinos] reported by commanding

officers is 14,643 killed and 3,297 wounded.... As to the number of

Filipinos whose deaths were due to the incidents of war, sickness,

burning of habitations, etc., we have no information.

The comparative figures of killed and wounded - nearly five killed to

one wounded if we take only the official returns - are absolutely

convincing. When we examine them in detail and find the returns quoted

of many killed and often no wounded, only one conclusion is possible.

In the fiercest battles of the Civil War the proportion was as

follows: at Antietam, where we attacked: killed, 2,o00; wounded,

9,416; at Fredericksburg, where we charged again and again under a

withering fire of rifles and cannon: killed, I, 180; wounded, 9,028;

at Gettysburg, where two veteran armies joined in desperate battle:

killed, 2,834; wounded, 13,709; at Cold Harbor, where the carnage was

frightful: killed, 1,905; wounded, 10, 570.

In the recent Boer War the proportion is the same. At Magersfontein:

killed, I71; wounded, 691; at Colenso: killed, 50; wounded, 847. In

all battles from October, i899, to June, 1900: killed, 2,518; wounded,

11,405.

In no war where the usages of civilized warfare have been respected

has the number of killed approached the number of wounded more nearly

than these figures. The rule is generally about five wounded to one

killed. What shall we say of a war where the proportions are reversed?

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929

War Department says:

The aggregate killed and wounded [Filipinos] reported by commanding

officers is 14,643 killed and 3,297 wounded.... As to the number of

Filipinos whose deaths were due to the incidents of war, sickness,

burning of habitations, etc., we have no information.

The comparative figures of killed and wounded - nearly five killed to

one wounded if we take only the official returns - are absolutely

convincing. When we examine them in detail and find the returns quoted

of many killed and often no wounded, only one conclusion is possible.

In the fiercest battles of the Civil War the proportion was as

follows: at Antietam, where we attacked: killed, 2,o00; wounded,

9,416; at Fredericksburg, where we charged again and again under a

withering fire of rifles and cannon: killed, I, 180; wounded, 9,028;

at Gettysburg, where two veteran armies joined in desperate battle:

killed, 2,834; wounded, 13,709; at Cold Harbor, where the carnage was

frightful: killed, 1,905; wounded, 10, 570.

In the recent Boer War the proportion is the same. At Magersfontein:

killed, I71; wounded, 691; at Colenso: killed, 50; wounded, 847. In

all battles from October, i899, to June, 1900: killed, 2,518; wounded,

11,405.

In no war where the usages of civilized warfare have been respected

has the number of killed approached the number of wounded more nearly

than these figures. The rule is generally about five wounded to one

killed. What shall we say of a war where the proportions are reversed?

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929

American fury n the Philippines. XXXII / Loboo

BATANGAS, Dec. 26, I901.

I have become convinced that within two months at the outside there

will be no more insurrection in this brigade. We may not have secured

all the guns or caught all the insurgents by that time, and the

present insurrection will end and the men and the guns will be secured

in time.... I am practically sure they cannot remain here in Batangas,

Laguna, and a part of Tayabas. The people are now assembled in the

towns, with all the visible food supply except that cached by

insurgents in the mountains. For the next six days all station

commanders will be employed hunting insurgents and their hidden food

supplies within their respective jurisdictions. Population of each

town will be turned out, and all transportation that can be found

impressed to bring into government storehouses all food that is found,

if it be possible to transport it. If not, it will be destroyed.

I am now assembling in the neighborhood of twenty-five hundred men,

who will be used in columns of about fifty men each. I expect to

accompany the command. Of course, no such strength is necessary to

cope with all the insurgents in the Philippine Islands, but the

country is indescribably rough and badly cut up.... To the ravines and

mountains I take so large a command for the purpose of thoroughly

searching each ravine, valley, and mountain-peak for insurgents and

for food, expecting to destroy everything I find outside of town,. All

able-bodied men will be killed or captured. Old men, women, and

children will be sent to towns. This movement begins January x, by

which time I hope to have nearly all the food supply in the towns. If

insurgents hide their guns and come into the towns, it will be to my

advantage; for I shall put such a pressure on town officials and

police that they will be compelled to identify insurgents.t If I catch

these, I shall get their guns in time. I expect to first clean out the

wide Loboo Peninsula south of Bantangas, Tiasan, and San Juan de Boc

Boc road. I shall then move command to the vicinity of Lake Taal, and

sweep the country westward to the ocean and south of Cavite, returning

through Lipa.

I shall scour and clean up the Lipa Mountains. Swinging northward, the

country in the vicinity of San Pablo, Alaminos, Tananan, and Santo

Tomas, will be scoured, ending at Mount Maguiling, which will then be

thoroughly searched and devastated. This is said to be the home of

Malvar and his parents.

Swinging back to the right, the same treatment will be given all the

country of which Mount Cristobal and Mount Banabao are the main peaks.

These two mountains, Mount Maguiling, and the mountains north-east of

Loboo are the main haunts of the insurgents. After the 1rst of January

no one will be permitted to move about without a pass....

These people need a thrashing to teach them some good common sense,

and they should have it for the good of all concerned. Sixto Lopez is

now interested in peace because I have in jail all the male members of

his family found in my jurisdiction, and have seized his houses and

palay and his steamer.

General Bell

I have become convinced that within two months at the outside there

will be no more insurrection in this brigade. We may not have secured

all the guns or caught all the insurgents by that time, and the

present insurrection will end and the men and the guns will be secured

in time.... I am practically sure they cannot remain here in Batangas,

Laguna, and a part of Tayabas. The people are now assembled in the

towns, with all the visible food supply except that cached by

insurgents in the mountains. For the next six days all station

commanders will be employed hunting insurgents and their hidden food

supplies within their respective jurisdictions. Population of each

town will be turned out, and all transportation that can be found

impressed to bring into government storehouses all food that is found,

if it be possible to transport it. If not, it will be destroyed.

I am now assembling in the neighborhood of twenty-five hundred men,

who will be used in columns of about fifty men each. I expect to

accompany the command. Of course, no such strength is necessary to

cope with all the insurgents in the Philippine Islands, but the

country is indescribably rough and badly cut up.... To the ravines and

mountains I take so large a command for the purpose of thoroughly

searching each ravine, valley, and mountain-peak for insurgents and

for food, expecting to destroy everything I find outside of town,. All

able-bodied men will be killed or captured. Old men, women, and

children will be sent to towns. This movement begins January x, by

which time I hope to have nearly all the food supply in the towns. If

insurgents hide their guns and come into the towns, it will be to my

advantage; for I shall put such a pressure on town officials and

police that they will be compelled to identify insurgents.t If I catch

these, I shall get their guns in time. I expect to first clean out the

wide Loboo Peninsula south of Bantangas, Tiasan, and San Juan de Boc

Boc road. I shall then move command to the vicinity of Lake Taal, and

sweep the country westward to the ocean and south of Cavite, returning

through Lipa.

I shall scour and clean up the Lipa Mountains. Swinging northward, the

country in the vicinity of San Pablo, Alaminos, Tananan, and Santo

Tomas, will be scoured, ending at Mount Maguiling, which will then be

thoroughly searched and devastated. This is said to be the home of

Malvar and his parents.

Swinging back to the right, the same treatment will be given all the

country of which Mount Cristobal and Mount Banabao are the main peaks.

These two mountains, Mount Maguiling, and the mountains north-east of

Loboo are the main haunts of the insurgents. After the 1rst of January

no one will be permitted to move about without a pass....

These people need a thrashing to teach them some good common sense,

and they should have it for the good of all concerned. Sixto Lopez is

now interested in peace because I have in jail all the male members of

his family found in my jurisdiction, and have seized his houses and

palay and his steamer.

General Bell

American fury in the Philippines. XXXI / Luzón

The Boston Advertiser is a Republican newspaper, and in its columns

appeared this statement:

- The time has come, in the opinion of those in charge of the War

Department, to pursue a policy of absolute and relentless subjugation

in the Philippine Islands. If the natives refuse to submit to the

process of government as mapped out by the Taft Commission, they will

be hunted down and will be killed until there is no longer any show of

forcible resistance to the American government. The process will not

be pleasant, but it is considered necessary.

Who has been the person in charge of the War Department ever since

the Taft Commission was appointed, and has not this statement been

proved to be true by what has happened since? On May 3, I9oI, General

James M. Bell, in an interview printed in the New York Times, said:

One-sixth of the natives of Luzon have either been killed or died of

the dengue fever in the last two years;

and, as Senator Hoar said, I suppose that this dengue fever and the

sickness which depopulated Batangas is the direct result of the war,

and comes from the condition of starvation and bad food which the war

has caused. General Bell is a witness whom the War Department cannot

discredit. " One-sixth of the population of Luzon "- one in every six

of men, women, and children - had either been killed or died in two

years. This means 666,ooo people. The population of Luzon is estimated

by the War Department to be 3,727,488 persons.* How many were killed,

and how? General Bell gave a suggestive answer when he said as a part

of the same statement:

The loss of life by killing alone has been very great, but I think not

one man has been slain except where his death served the legitimate

purpose of war. It has been thought necessary to adopt what in other

countries would probably be thought harsh measures.

A Republican Congressman, who visited the Philippines during the

summer of 1901, confirms this answer in an interview published in the

Boston Transcript, and in other newspapers, on March 4, 1902:

You never hear of any disturbances in Northern Luzon; and the secret

of its pacification is, in my opinion, the secret of the pacification

of the archipelago. They never rebel in Northern Luzon because there

isn't anybody there to rebel. The country was marched over and cleaned

out in a most resolute manner. The good Lord in heaven only knows the

number of Filipinos that were put under ground. Our soldiers took no

prisoners, they kept no records; they simply swept the country, and,

wherever or whenever they could get hold of a Filipino, they killed

him. The women and children were spared, and may now be noticed in

disproportionate numbers in -that part of the island. Thus did we here

protect " the patient... millions."

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

appeared this statement:

- The time has come, in the opinion of those in charge of the War

Department, to pursue a policy of absolute and relentless subjugation

in the Philippine Islands. If the natives refuse to submit to the

process of government as mapped out by the Taft Commission, they will

be hunted down and will be killed until there is no longer any show of

forcible resistance to the American government. The process will not

be pleasant, but it is considered necessary.

Who has been the person in charge of the War Department ever since

the Taft Commission was appointed, and has not this statement been

proved to be true by what has happened since? On May 3, I9oI, General

James M. Bell, in an interview printed in the New York Times, said:

One-sixth of the natives of Luzon have either been killed or died of

the dengue fever in the last two years;

and, as Senator Hoar said, I suppose that this dengue fever and the

sickness which depopulated Batangas is the direct result of the war,

and comes from the condition of starvation and bad food which the war

has caused. General Bell is a witness whom the War Department cannot

discredit. " One-sixth of the population of Luzon "- one in every six

of men, women, and children - had either been killed or died in two

years. This means 666,ooo people. The population of Luzon is estimated

by the War Department to be 3,727,488 persons.* How many were killed,

and how? General Bell gave a suggestive answer when he said as a part

of the same statement:

The loss of life by killing alone has been very great, but I think not

one man has been slain except where his death served the legitimate

purpose of war. It has been thought necessary to adopt what in other

countries would probably be thought harsh measures.

A Republican Congressman, who visited the Philippines during the

summer of 1901, confirms this answer in an interview published in the

Boston Transcript, and in other newspapers, on March 4, 1902:

You never hear of any disturbances in Northern Luzon; and the secret

of its pacification is, in my opinion, the secret of the pacification

of the archipelago. They never rebel in Northern Luzon because there

isn't anybody there to rebel. The country was marched over and cleaned

out in a most resolute manner. The good Lord in heaven only knows the

number of Filipinos that were put under ground. Our soldiers took no

prisoners, they kept no records; they simply swept the country, and,

wherever or whenever they could get hold of a Filipino, they killed

him. The women and children were spared, and may now be noticed in

disproportionate numbers in -that part of the island. Thus did we here

protect " the patient... millions."

Title: Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine

warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and

utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root.

Author: Storey, Moorfield, 1845-1929.

May 24, 2008

American fury in the Philippines. XXX / Panay

Letter of Mr. Nelson is in the Boston Herald of August 25, 1902

...There is probably no island in the archipelago where it was used

oftener and with better effect than in Panay.... When General Hughes

began his vigorous campaign, Panay was one of the worst of the

islands: to-day it is one of the best.... And there seems to be no

doubt that these conditions are due to the stern measures adopted to

crush out guerilla warfare and ladronism. There was talk of

promiscuous burning in connection with General Smith. Let me tell you

what it really means when you can see it. The Eighteenth Regulars

marched from Iloilo in the south to Capiz in the north of Panay, under

orders to burn every town from which they were attacked. The result

was they left a strip of land sixty miles wide from one end of the

island to the other, over which the traditional crow could not have

flown without provisions. That is what burning means, and no more.

...There is probably no island in the archipelago where it was used

oftener and with better effect than in Panay.... When General Hughes

began his vigorous campaign, Panay was one of the worst of the

islands: to-day it is one of the best.... And there seems to be no

doubt that these conditions are due to the stern measures adopted to

crush out guerilla warfare and ladronism. There was talk of

promiscuous burning in connection with General Smith. Let me tell you

what it really means when you can see it. The Eighteenth Regulars

marched from Iloilo in the south to Capiz in the north of Panay, under

orders to burn every town from which they were attacked. The result

was they left a strip of land sixty miles wide from one end of the

island to the other, over which the traditional crow could not have

flown without provisions. That is what burning means, and no more.

American fury in the Philippines. XXIX / Extermination

Letter of an officer who had served in the islands .

- There is no use mincing words. There are but two possible

conclusions to the matter. We must conquer and hold the islands or get

out. The question is, Which shall it be? If we decide to stay, we must

bury all qualms and scruples about Weylerian cruelty, the consent of

the governed, etc., and stay. We exterminated the American Indians,

and I guess most of us are proud of it, or, at least, believe the end

justified the means; and we must have no scruples about exterminating

this other race standing in the way of progress and enlightenment, if

it is necessary.

- There is no use mincing words. There are but two possible

conclusions to the matter. We must conquer and hold the islands or get

out. The question is, Which shall it be? If we decide to stay, we must

bury all qualms and scruples about Weylerian cruelty, the consent of

the governed, etc., and stay. We exterminated the American Indians,

and I guess most of us are proud of it, or, at least, believe the end

justified the means; and we must have no scruples about exterminating

this other race standing in the way of progress and enlightenment, if

it is necessary.

American fury in the Philippines. XXVIII

Senator RAWLINS. If these shacks were of no consequence what was the

utility of their destruction?

General HUGHES

S. The destruction was as a punishment. They permitted these people to

come in there and conceal themselves and they gave no sign. It is always _

Senator RAWLINS. The punishment in that case would fall, not upon the

men, who could go elsewhere, but mainly upon the women and little

children.

General HUGHES. The women and children are part of the family, and

where you wish to inflict a punishment you can punish the man probably

worse in that way than in any other.

Senator RAWLINS. But is that within the ordinary rules of civilized

warfare? Of course you could exterminate the family, which would be

still worse punishment.

General HUGHES. These people are not civilized.

Senator RAWLINS. Then I understand you to say it is not civilized

warfare?

General HUGHES. No: I think it is not.

Senator RAWLINS. Is it not true that operations in the islands became

progressively more severe within the past year and a half in dealing

with districts which were disturbed?

General HUGHES. I think that is true. I would not say it is entirely

so. The severities depend upon the man immediately in command of the

force that he has with him. In the department I suppose I had at times

as many as a hundred and twenty commands in the field. Each commander,

under general restrictions, had authority to act for himself. These

commanders were changed from time to time. The new commanders coming

in would probably start in very much easier than the old ones.

Senator HALE. Very much what?

General HUGHES. Easier. They would come from this country with their

ideas of civilized warfare, and they were allowed to get their lesson.

utility of their destruction?

General HUGHES

S. The destruction was as a punishment. They permitted these people to

come in there and conceal themselves and they gave no sign. It is always _

Senator RAWLINS. The punishment in that case would fall, not upon the

men, who could go elsewhere, but mainly upon the women and little

children.

General HUGHES. The women and children are part of the family, and

where you wish to inflict a punishment you can punish the man probably

worse in that way than in any other.

Senator RAWLINS. But is that within the ordinary rules of civilized

warfare? Of course you could exterminate the family, which would be

still worse punishment.

General HUGHES. These people are not civilized.

Senator RAWLINS. Then I understand you to say it is not civilized

warfare?

General HUGHES. No: I think it is not.

Senator RAWLINS. Is it not true that operations in the islands became

progressively more severe within the past year and a half in dealing

with districts which were disturbed?

General HUGHES. I think that is true. I would not say it is entirely

so. The severities depend upon the man immediately in command of the

force that he has with him. In the department I suppose I had at times

as many as a hundred and twenty commands in the field. Each commander,

under general restrictions, had authority to act for himself. These

commanders were changed from time to time. The new commanders coming

in would probably start in very much easier than the old ones.

Senator HALE. Very much what?

General HUGHES. Easier. They would come from this country with their

ideas of civilized warfare, and they were allowed to get their lesson.

American fury in the Philippines. XXVII / Marilao

The special correspondent of the Boston Transcript, as early as April

14, 1899, wrote from Marilao:

"Just watch our smoke " is what the Minnesota and Oregon regiments

have adopted for a motto since their experiences of the last few days.

Their trail was eight miles long; and the smoke of burning buildings

and rice heaps rose into the heaven the entire distance, and obscured

the face of the landscape for many hours. They started at daylight

this morning, driving the rebels before them and setting the torch to

everything burnable in their course. This was in retaliation for a

night attack."

14, 1899, wrote from Marilao:

"Just watch our smoke " is what the Minnesota and Oregon regiments

have adopted for a motto since their experiences of the last few days.

Their trail was eight miles long; and the smoke of burning buildings

and rice heaps rose into the heaven the entire distance, and obscured

the face of the landscape for many hours. They started at daylight

this morning, driving the rebels before them and setting the torch to

everything burnable in their course. This was in retaliation for a

night attack."

American fury in the Philippines. XXVI / Reconcentration

Here is testimony from another source as to an undoubted concentration

camp. It comes through Senator Bacon, of Georgia, from whose speech in

the Senate the following extract is taken:Mr. President, I want to

read to you a description of a reconcentrado camp. I will say that

this letter is written by an officer whom I know personally, and for

whom I vouch in my place in the Senate as a high-toned man and a

courageous and chivalric officer, one who does his duty regardless of

whether he approves of the cause in which he is told to fight or not,

and one in every way worthy of confidence and esteem. This was a

letter written by him with no injunction of secrecy in it, because he

had no idea or thought that it would ever be made public. I make it

public now simply for the information of the Senate, in order that

they may have some idea of what a reconcentrado camp is. I omit the

name of the place from which the letter was written for the same

reason that I omit the name of the officer. I will not say any more of

him than that he is a graduate of West Point and a professional

soldier. I will state further that there is some allusion in the

letter to vampires. A vampire in those islands is a bird about the

size of a crow, which wheels and circles above the head at night, and

which is plainly visible at night. As I have said, I know the officer

personally and vouch for him in every way. Senators will see from the

reading of this letter that it is simply the casual and ordinary

narration of a friend writing to a friend. He says: — " On our way

over here we stopped at - in peaceful - to leave our surplus stuff so

as to get into "I have left out these names - "light shape; and, as we

landed at midnight there, they weren't satisfied with bolos and

shotguns, but little brown brother actually fired upon us with brass

cannon in that officially quiet burg under efficient civil government.

What a farce it all is " That is his comment on that fact. "Well,

consider, ten miles and over down the coast, we found a great deposit

of mud just off the mouth of the river, and after waiting eight hours

managed to get over the bar without being stuck but three times - and

the tug drew three feet. " Then eight miles up a slimy, winding bayou

of a river until at 4 A.M. we struck a piece of spongy ground about

twenty feet above the sea-level. Now you have us located. It rains

continually in a way that would have made Noah marvel. And trails, if

you can find one, make the 'Slough of Despond' seem like an asphalt

pavement. Now this little spot of black sogginess is a reconcentrado

pen, with a dead-line outside, beyond which everything living is shot.

"This corpse-carcass stench wafted in and combined with some lovely

municipal odors besides makes it slightly unpleasant here. " Upon

arrival I found thirty cases of small-pox and average fresh ones of

five a day, which practically have to be turned out to die. At

nightfall clouds of huge vampire bats softly swirl out on their orgies

over the dead. "Mosquitoes work in relays, and keep up their pestering

day and night. There is a pleasing uncertainty as to your being boloed

before morning or being cut down in the long grass or sniped at. It

seems way out of the world without a sight of the sea,- in fact, more

like some suburb of hell."

camp. It comes through Senator Bacon, of Georgia, from whose speech in

the Senate the following extract is taken:Mr. President, I want to

read to you a description of a reconcentrado camp. I will say that

this letter is written by an officer whom I know personally, and for

whom I vouch in my place in the Senate as a high-toned man and a

courageous and chivalric officer, one who does his duty regardless of

whether he approves of the cause in which he is told to fight or not,

and one in every way worthy of confidence and esteem. This was a

letter written by him with no injunction of secrecy in it, because he

had no idea or thought that it would ever be made public. I make it

public now simply for the information of the Senate, in order that

they may have some idea of what a reconcentrado camp is. I omit the

name of the place from which the letter was written for the same

reason that I omit the name of the officer. I will not say any more of

him than that he is a graduate of West Point and a professional

soldier. I will state further that there is some allusion in the

letter to vampires. A vampire in those islands is a bird about the

size of a crow, which wheels and circles above the head at night, and

which is plainly visible at night. As I have said, I know the officer

personally and vouch for him in every way. Senators will see from the

reading of this letter that it is simply the casual and ordinary

narration of a friend writing to a friend. He says: — " On our way

over here we stopped at - in peaceful - to leave our surplus stuff so

as to get into "I have left out these names - "light shape; and, as we

landed at midnight there, they weren't satisfied with bolos and

shotguns, but little brown brother actually fired upon us with brass

cannon in that officially quiet burg under efficient civil government.

What a farce it all is " That is his comment on that fact. "Well,

consider, ten miles and over down the coast, we found a great deposit

of mud just off the mouth of the river, and after waiting eight hours

managed to get over the bar without being stuck but three times - and

the tug drew three feet. " Then eight miles up a slimy, winding bayou

of a river until at 4 A.M. we struck a piece of spongy ground about

twenty feet above the sea-level. Now you have us located. It rains

continually in a way that would have made Noah marvel. And trails, if

you can find one, make the 'Slough of Despond' seem like an asphalt

pavement. Now this little spot of black sogginess is a reconcentrado

pen, with a dead-line outside, beyond which everything living is shot.

"This corpse-carcass stench wafted in and combined with some lovely

municipal odors besides makes it slightly unpleasant here. " Upon

arrival I found thirty cases of small-pox and average fresh ones of

five a day, which practically have to be turned out to die. At

nightfall clouds of huge vampire bats softly swirl out on their orgies

over the dead. "Mosquitoes work in relays, and keep up their pestering

day and night. There is a pleasing uncertainty as to your being boloed

before morning or being cut down in the long grass or sniped at. It

seems way out of the world without a sight of the sea,- in fact, more

like some suburb of hell."

American fury in the Philippines. XXV / Torture

Manila Times of March 5, 1902.

" In several instances natives who were captured were tied to trees

and submitted to a series of slow tortures that finally resulted in

death, in some instances the victims living for three or four days.

The treatment was the most cruel and brutal imaginable. Natives were

tied to trees, and, in order to make them give confession, they were

shot through the legs and left thus to suffer trough the night, only

to be given a repetition of the treatment the next day, in some

instances the treatment lasting as long as four days before the

miserable creatures were relieved by death."

" In several instances natives who were captured were tied to trees

and submitted to a series of slow tortures that finally resulted in

death, in some instances the victims living for three or four days.

The treatment was the most cruel and brutal imaginable. Natives were

tied to trees, and, in order to make them give confession, they were

shot through the legs and left thus to suffer trough the night, only

to be given a repetition of the treatment the next day, in some

instances the treatment lasting as long as four days before the

miserable creatures were relieved by death."

American fury in the Philippines. XXIV / Samar

[Circular No. 6.]

HEADQUARTERS SIXTH SEPARATE BRIGADE, TACLOBAN, LEYTE-, P.I., Dec. 24,

1901.

To All Station Commanders:

The brigade commander has become thoroughly convinced from the great

mass of evidence at hand that the insurrection for some time past and

still in force in the island of Samar has been supported solely by the

people who live in the pueblos ostensibly pursuing their peaceful

pursuits and enjoying American protection, and that this is especially

true in regard to the "pudientes," or wealthy class. He is and for

some time past has been satisfied that the people themselves, and

especially this wealthy and influential class, can stop this

insurrection at any time they make up their minds to do so; that up to

the present time they do not want peace; that they are working in

every way and to the utmost of their ability to prevent peace. He is

satisfied that this class, while openly talking peace, is doing so

simply to gain the confidence of our officers and soldiers, only to

betray them to the insurrectos, or, in short, that while ostensibly

aiding the Americans, they are in reality secretly doing everything in

their power to support and maintain this insurrection. Under such

conditions there can be but one course to pursue, which is to adopt

the policy that will create in the minds of all the people a burning

desire for the war to cease,- a desire or longing so intense, so

personal especially to every individual of the class mentioned, and so

real that it will impel them to devote themselves in earnest to

bringing about a state of real peace, that will impel them to join

hands with the Americans in the accomplishment of this end. The policy

to be pursued in this brigade, from this time on, will be to wage war

in the sharpest and most decisive manner possible. This policy will

apply to the island of Samar and such other portions of the brigade to

which it may become necessary to apply it, even though such territory

is supposedly peaceful or is under civil government. In waging this

warfare, officers of this brigade are directed and expected to

co-operate to their utmost, so as to terminate this war as soon as

practicable, since short severe wars are the most humane in the end.

No civilized war, however civilized, can be carried on on a

humanitarian basis. In waging this war, officers will be guided by the

provisions of General Orders, No. o00, Adjutant-general's Office,

1863, which order promulgates the instructions for the government of

the armies of the United States in the field. (Copies of this order

will be furnished to the troops of this brigade as soon as

practicable. In the mean time commanding officers will personally see

to it that the younger and less experienced officers of the command

are instructed in the provisions of this order, wherever it is

possible to do so.)

Commanding officers are earnestly requested and expected to exercise,

without reference to these headquarters, their own discretion in the

adoption of any and all measures of warfare coming within the

provisions of this general order which will tend to accomplish the

desired results in the most direct way or in the shortest possible

space of time.They will also encourage the younger officers of their

commands to constantly look for, engage, harass, and annoy the enemy

in the field; and to this end commanding officers will repose a large

amount of confidence in these subordinate officers, and will permit to

them a large latitude of action and a discretion similar to that

herein conferred upon the commanding officers of stations by these

headquarters. In dealing with the natives of all classes, officers

will be guided by the following principles:

First. Every native, whether in arms or living in the pueblos or

barrios, will be regarded and treated as an enemy until he has

conclusively shown that he is a friend. This he cannot do by mere

words or promises, nor by imparting information which, while true, is

old or stale and of no value; nor can it be done by aiding us in ways

that do no material harm to the insurgents. In short, the only manner

in which the native can demonstrate his loyalty is by some positive

act or acts that actually and positively commit him to us, thereby

severing his relations with the insurrectos and producing or tending

to produce distinctively unfriendly relations with the insurgents. Not

only the ordinary natives, but especially those of influence and

position in the pueblos, who manifestly and openly cultivate friendly

relations with the Americans, will be regarded with particular

suspicion, since by the announced policy of the insurgent government

their ablest and most stanch friends or those who are capable of most

skilfully practising duplicity are selected and directed to cultivate

the friendship of American officers, so as to obtain their confidence,

and to secretly communicate to the insurgents everything that the

Americans do or contemplate doing, particularly with regard to the

movement of troops. In a word, friendship for the Americans on the

part of any native will be measured directly and solely by his acts;

and neither sentiment nor social reasons of any kind will be permitted

to enter into the determination of such friendship.

Second. It will be regarded as a certainty that all officials of the

pueblos and barrios are likewise officials of Lukban and his officers,

or at least that they are in actual touch and sympathy with the

insurgent leaders, and that they are in secret aiding these leaders

with information, supplies, etc., wherever possible. Officers will not

be misled by the fact that officials of the pueblos pass ordinances

inimical to those in insurrection, or by any action taken by them,

either collectively or individually. The public acts of pueblo

councils that are favorable to the Americans are usually negative by

secret communication on the part of the parties enacting them to those

in insurrection. Therefore, such acts cannot be taken as a guide in

determining the friendship or lack of it of these officials for the

American government.

Third. The taking of the oath of allegiance by officials, presidentes,

vice-presidentes, consejeros, principales, tenientes of barrios, or

other people of influence, does not indicate that they or any of them

have espoused the American cause, since it is a well-established fact

that these people frequently take the oath of allegiance with the

direct object and intent of enabling them to be of greater service to

their real friends in the field. In short, the loyalty of these people

is to be determined only by acts which, when combined with their usual

course of conduct, irrevocably binds them to the American cause.

Neutrality must not be tolerated on the part of any native. The time

has now arrived when all natives in this brigade, who are not openly

for us must be regarded as against us. In short, if not an active

friend, he is an open enemy.

Fourth. The most dangerous class with whom we have to deal is the

wealthy sympathizer and contributor. This class comprises not only all

those officials and principales above mentioned, but all those of

importance who live in the pueblos with their families. By far the

most important as well as the most dangerous member of this class is

the native priest. He is most dangerous; and he is successful because

he is usually the best informed, besides wielding an immense influence

with the people by virtue of his position. He has much to lose, in his

opinion, and but little to gain through American supremacy in these

island. It is expected that officers will exercise their best

endeavors to suppress and prevent aid being given by the people of

this class, especially by the native priests. Wherever there is

evidence of this assistance, or where there is a strong suspicion that

they are thus secretly aiding the enemies of our government, they will

be confined and held. The profession of the priest will not prevent

his arrest or proceedings against him. If the evidence is sufficient,

they,will be tried by the proper court. If there is not sufficient

evidence to convict, they will be arrested and confined as a military

necessity, and held as prisoners of war until released by orders from

these headquarters. It will be borne in mind that in these islands, as

a rule, it is next to impossible to secure evidence against men of

influence, and especially against the native priests, so long as they

are at large. On the other hand, after they are arrested and confined,

it is usually quite easy to secure abundant evidence against them.

Officers in command of stations will not hesitate, therefore, to

arrest and detain individuals whom they have good reasons to suspect

are aiding the insurrection, even when positive evidence is lacking....

HEADQUARTERS SIXTH SEPARATE BRIGADE, TACLOBAN, LEYTE-, P.I., Dec. 24,

1901.

To All Station Commanders:

The brigade commander has become thoroughly convinced from the great

mass of evidence at hand that the insurrection for some time past and

still in force in the island of Samar has been supported solely by the

people who live in the pueblos ostensibly pursuing their peaceful

pursuits and enjoying American protection, and that this is especially

true in regard to the "pudientes," or wealthy class. He is and for

some time past has been satisfied that the people themselves, and

especially this wealthy and influential class, can stop this

insurrection at any time they make up their minds to do so; that up to

the present time they do not want peace; that they are working in

every way and to the utmost of their ability to prevent peace. He is

satisfied that this class, while openly talking peace, is doing so

simply to gain the confidence of our officers and soldiers, only to

betray them to the insurrectos, or, in short, that while ostensibly

aiding the Americans, they are in reality secretly doing everything in

their power to support and maintain this insurrection. Under such

conditions there can be but one course to pursue, which is to adopt

the policy that will create in the minds of all the people a burning

desire for the war to cease,- a desire or longing so intense, so

personal especially to every individual of the class mentioned, and so

real that it will impel them to devote themselves in earnest to

bringing about a state of real peace, that will impel them to join

hands with the Americans in the accomplishment of this end. The policy

to be pursued in this brigade, from this time on, will be to wage war

in the sharpest and most decisive manner possible. This policy will

apply to the island of Samar and such other portions of the brigade to

which it may become necessary to apply it, even though such territory

is supposedly peaceful or is under civil government. In waging this

warfare, officers of this brigade are directed and expected to

co-operate to their utmost, so as to terminate this war as soon as

practicable, since short severe wars are the most humane in the end.

No civilized war, however civilized, can be carried on on a

humanitarian basis. In waging this war, officers will be guided by the

provisions of General Orders, No. o00, Adjutant-general's Office,

1863, which order promulgates the instructions for the government of

the armies of the United States in the field. (Copies of this order

will be furnished to the troops of this brigade as soon as

practicable. In the mean time commanding officers will personally see

to it that the younger and less experienced officers of the command

are instructed in the provisions of this order, wherever it is

possible to do so.)

Commanding officers are earnestly requested and expected to exercise,

without reference to these headquarters, their own discretion in the

adoption of any and all measures of warfare coming within the

provisions of this general order which will tend to accomplish the

desired results in the most direct way or in the shortest possible

space of time.They will also encourage the younger officers of their

commands to constantly look for, engage, harass, and annoy the enemy

in the field; and to this end commanding officers will repose a large

amount of confidence in these subordinate officers, and will permit to

them a large latitude of action and a discretion similar to that

herein conferred upon the commanding officers of stations by these